Bengali, Spoken and Written. Sayamacharan Ganguli (1877). কিস্তি ২ ।।

- বাঙ্গালা ভাষা ।। লিখিবার ভাষা* Рবঙ্কিমচন্দ্র চট্টোপাধ্যায় [১৮৬৪]

- Bengali, Spoken and Written. Sayamacharan Ganguli (1877). কিস্তি ১

- Bengali, Spoken and Written. Sayamacharan Ganguli (1877). কিস্তি ২ ।।

- Bengali, Spoken and Written. Sayamacharan Ganguli (1877). শেষ কিস্তি ।।

- বাঙ্গালা ভাষা Рগ্রাডুএট্ (হরপ্রসাদ শাস্ত্রী) [১৮৮১]

- একখানি পুরাতন দলিল: আবদুল করিম [১৯০৬]

- আমাদের ভাষাসমস্যা Рমুহম্মদ শহীদুল্লাহ্ (১৯১৭)

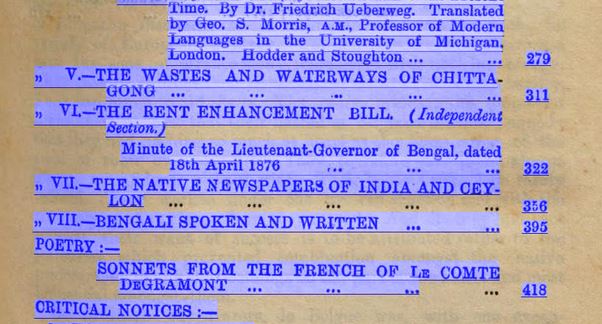

- ‚Äú‡¶Æ‡ßҶ∏‡¶≤‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶®‡ßÄ ‡¶¨‡¶æ‡¶ô‡ß燶ó‡¶æ‡¶≤‡¶æ” ‡¶ï‡¶ø? – ‡¶Ü‡¶¨‡¶¶‡ßҶ≤ ‡¶ï‡¶∞‡¶ø‡¶Æ ‡¶∏‡¶æ‡¶π‡¶ø‡¶§‡ß燶؇¶¨‡¶ø‡¶∂‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶¶

- বাঙ্গালা বানান সমস্যা (১৯৩১) Рমুহম্মদ শহীদুল্লাহ্

- বাংলাভাষা পরিচয় Рরবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর [১৯৩৮]

- পূর্ব পাকিস্তানের রাষ্ট্রভাষা ।। সৈয়দ মুজতবা আলী।। কিস্তি ১ ।।

- পূর্ব পাকিস্তানের রাষ্ট্রভাষা ।। সৈয়দ মুজতবা আলী।। কিস্তি ২ ।।

- পূর্ব পাকিস্তানের রাষ্ট্রভাষা ।। সৈয়দ মুজতবা আলী।। কিস্তি ৩।।

- পূর্ব পাকিস্তানের রাষ্ট্রভাষা ।। সৈয়দ মুজতবা আলী।। শেষ কিস্তি।।

- আমাদের ভাষা ।। আবুল মনসুর আহমেদ ।। ১৯৫৮ ।।

- আঞ্চলিক ভাষার অভিধান [১৯৬৪] : সৈয়দ আলী আহসান ও মুহম্মদ শহীদুল্লাহ্‌র ভাষা প্ল্যানিং

- (বই থেকে) স্বাতন্ত্রের স্বীকৃতি এবং রাষ্ট্রিক বনাম কৃষ্টিক স্বাধীনতা Рআবুল মনসুর আহমদ (১৯৬৮)

- বাংলা প্রচলিত হবে যে সময় শিক্ষকরা প্রথম প্রথম একটু ইনকমপিটেনটলি (incompetently) কিন্তু পারসিসটেনটলি (persistently) বাংলায় বলা অভ্যাস করবেন (১৯৮৫) Рআবদুর রাজ্জাক

- বাংলা ভাষার আধুনিকায়ন: ভাষিক ঔপনিবেশিকতা অথবা উপনিবেশিত ভাষা

- বাংলা ভাষা নিয়া কয়েকটা নোকতা

- খাশ বাংলার ছিলছিলা

- বাছবিচার আলাপ: খাশ বাংলা কি ও কেন? [২০২২]

কিস্তি ১

……………………………………………………………

‡¶ó‡ß燶∞‡¶æ‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶∞‡ßᇶ∞ ‡¶Ø‡ßá ‡¶Æ‡ßᇶú‡¶∞ ‡¶ú‡¶æ‡ßü‡¶ó‡¶æ‡¶ó‡ßҶ≤‡¶ø – ‡¶∏‡¶®‡ß燶߇¶ø, ‡¶∏‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶∏ ‡¶è‡¶á‡¶∏‡¶¨ ‡¶ú‡¶æ‡ßü‡¶ó‡¶æ‡¶§‡ßá ‡¶∂‡ß燶؇¶æ‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶ö‡¶∞‡¶£ ‡¶¶‡ßᇶñ‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ® ‡¶Ø‡ßá, ‡¶∏‡¶Ç‡¶∏‡ß燶ï‡ßɇ¶§‡ßᇶ∞ ‡¶®‡¶ø‡ßü‡¶Æ ‡¶∞‡¶æ‡¶ñ‡¶æ‡¶∞ ‡¶ï‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶£‡ßá ‡¶ó‡ßㇶ≤‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶≤ ‡¶π‡¶á‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßá, ‡¶ï‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶£ ‡¶è‡¶á‡¶ó‡ßҶ≤‡¶ø ‡¶∞‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶ü‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶ú‡ßㇶ∞ ‡¶ï‡¶á‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶¢‡ßŇ¶ï‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ®, ‡¶¨‡ßᇶ∂‡¶ø‡¶∞‡¶≠‡¶æ‡¶ó ‡¶∏‡¶Æ‡ßü‡•§ ‡¶∞‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶ü‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶Ü‡¶∞‡ßã ‡¶Ü‡¶ï‡¶æ‡¶Æ ‡¶ï‡¶∞‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ®, ‡¶Ø‡ßá‡¶á ‡¶∂‡¶¨‡ß燶¶‡¶ó‡ßҶ≤‡¶æ ‡¶∏‡¶Ç‡¶∏‡ß燶ï‡ßɇ¶§ ‡¶•‡¶ø‡¶ï‡¶æ ‡¶ö‡ßᇶᇶû‡ß燶ú ‡¶π‡ßü‡¶æ ‡¶¨‡¶æ‡¶Ç‡¶≤‡¶æ‡ßü ‡¶Ü‡¶∏‡¶õ‡¶ø‡¶≤‡ßã ‡¶∏‡ßᇶᇶó‡ßҶ≤‡¶æ‡¶∞‡ßá ‡¶¨‡¶¶‡¶≤‡¶æ‡ßü‡¶æ ‡¶∏‡¶Ç‡¶∏‡ß燶ï‡ßɇ¶§ ‡¶ï‡¶á‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶¶‡¶ø‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ® ‡¶≤‡ßᇶñ‡¶æ‡¶∞ ‡¶Æ‡¶ß‡ß燶؇ßá, ‡¶≠‡¶æ‡¶á’‡¶∞‡ßá ‡¶≤‡¶ø‡¶ñ‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ® ‡¶≠‡ß燶∞‡¶æ‡¶§, ‡¶ï‡¶æ‡¶®’‡¶∞‡ßá ‡¶≤‡¶ø‡¶ñ‡¶§‡ßᇶõ‡ßᇶ® ‡¶ï‡¶∞‡ß燶£‡•§ ‡¶è‡¶á‡¶∏‡¶¨ ‡¶´‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶ú‡¶≤‡¶æ‡¶Æ‡¶ø ‡¶è‡¶ñ‡¶®‡ßã ‡¶Ü‡¶õ‡ßá, ‡¶≤‡ß燶؇¶æ‡¶Ç‡ßú‡¶æ‡¶∞‡ßá ‡¶â‡¶®‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶Ü‡¶¶‡¶∞ ‡¶ï‡¶á‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶≤‡ßᇶñ‡ßᇶ®, ‡¶ñ‡¶û‡ß燶ú‡•§ ‡¶è‡¶ï ‡¶è‡¶ï‡¶ü‡¶æ ‡¶≠‡¶æ‡¶∑‡¶æ ‡¶´‡ß燶؇¶æ‡¶∏‡¶ø‡¶¨‡¶æ‡¶¶‡¶ø ‡¶è‡¶á ‡¶∞‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶ü‡¶æ‡¶∞‡¶ó‡ßҶ≤‡¶æ, ‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶®‡ßá ‡¶ú‡ßㇶ∞ ‡¶ï‡¶á‡¶∞‡¶æ ‡¶®‡¶ø‡¶ú‡ßᇶ¶‡ßᇶ∞ ‡¶ú‡¶ø‡¶®‡¶ø‡¶∏ ‡¶ö‡¶æ‡¶™‡¶æ‡¶á‡¶§‡ßá ‡¶ö‡¶æ‡ßü‡•§ ‡¶∂‡ß燶؇¶æ‡¶Æ‡¶æ‡¶ö‡¶∞‡¶£ ‡¶Ø‡¶¶‡¶ø‡¶ì ‡¶ì‡¶á ‡¶è‡¶ï‡ß燶∏‡¶ü‡ßᇶ®‡ß燶° ‡¶§‡¶ï ‡¶¨‡¶ï‡¶æ‡¶¨‡¶ï‡¶ø ‡¶ï‡¶∞‡ßᇶ® ‡¶®‡¶æ‡¶á‡•§

কয়দিন পরে পরে নিউজ দেখবেন, অক্সফোর্ড ডিকশনারি এই শব্দ নিছে, ওই শব্দ নিছে। বাংলা একাডেমিতে এইটা এইরকম আছে, অইটা অইরকম। আরে, ডিকশনারি ওয়ার্ড নেয়ার কেডা? শব্দ তো আমরা কইলেই আছে আর না কইলে বাদই হয়া যাইতেছে, ডিকশনারির কামই হইতেছে কম্পাইল করা, আপডেট করা। ঘোড়ার আগে গাড়ি বসায়া দিলে কেমনে! তো, এই কারণে দেখবেন, পুলিশরে, সরকারি, বেসরকারি চাকর-বাকররে রেসপেক্ট করা লাগে আমরার, পাবলিকের। এদের কাম যে পাবলিকরে সার্ভ করা এই বেসিক জিনিসটাতেই আমরার বিশ্বাস নাই। যেই কারণে, ডিকশনারিরে অথরিটি মনেহয়, ভাষার। রাইটাররাও নিজেদেরকে মালিক মনে করতে পারে। এখন একজন রাইটার সংস্কৃত ক্যান গ্রীক, জার্মান, ফরাসী গ্রামার ফলো কইরা বাংলা লেখতে পারেন, এইটা যার যার ইচ্ছা। কিন্তু এইটাই বাংলা ভাষা Рএইরকম ক্লেইম করা তো যাইতে পারে না।

শ্যামচরণ উদাহারণ দিয়া কইতেছেন, এক “লোফা” শব্দরে সংস্কৃত রাইটার লেখতেছেন, “উৎক্ষেপ করিয়া পুর্নবার হাতে গ্রহণ করা”। এইগুলি কোন না-জানার ঘটনা বা কাব্যিকতা না, স্রেফ বাটপারি। এইসব সংস্কৃত রাইটাররা যেই শব্দ আমাদের বলার মধ্যে আছে তারে তো বাদ দিতেছেনই, আবার এমন এমন শব্দ আনতেছেন, যেইটার দরকারই নাই। এখন আরেক বাটপারি চলতেছে আঞ্চলিক শব্দ নাম দিয়া, যেন শব্দের কোন আঞ্চলিকতা নাই, আকাশ থিকা ফাল দিয়া পড়ে, নাজিল হয়!

মানে, ব্যাপারটা আমার কাছে ঠিক গ্রামার না, বরং গ্রামারের নিয়মগুলা যে কোন একটা চিন্তা থিকা আসতেছে সেইটা নিয়া ভাবতে পারাটা দরকারি। শ্যামাচরণ বলতেছেন, লেখার ভাষা কিছু নিয়ম বাইর করছে, মোস্টলি সংস্কৃতরে বাপ মাইনা আর সেইটার বাইরে যাইতে চাইতেছে না, যেইখানে যেইখানে বলার সাথে কম্পিটেবল না, সেইখানেও জবরদস্তি করতেছে। এইখানে আমার পয়েন্ট দুইটা। এক হইলো এই যে, কোন নিয়মরে সেন্টার ধরা, এইটাই একটা ভুল। ভাষারে বুঝার লাইগা নিয়ম আমরা বানাইতে পারি, কিন্তু নিয়মের বাইরে কোন ভাষা হইতে পারবে না – এইরকম ফতোয়া দেয়া পসিবলই না। দুসরা হইলো, এই যে নিয়ম মানা–ই লাগবো – এইটা চিন্তার জায়গাটারেও আরো আটকায়া দিতেছে।

গ্রামার দিয়া, সার্টেন নিয়ম দিয়া আমরা ভাষারে বুঝার ট্রাই করতে পারি, কিন্তু ভাষা গ্রামারের বাইরে যাইতে পারবো না – এইটা খালি বাকোয়াজি না, একটা ক্লিয়ারকাট বদমাইশি চিন্তা।

ই. হা.

……………………………………………………………

The subject of gender next calls for remark. In the living Bengali tongue there is no trace left of any artificial distinction of gender, hut in writing, this worst of encumbrances is sedulously kept up. If pritbibi (prithivi) is feminine in Sanskrit, it must be so perforce in Bengali, and this although the language has now utterly outgrown that stage of grammatical development in which there is an arbitrary assignment of gender to inanimate objects. Not only in assigning gender lo the names of lifeless things do Bengali writers seek to carry the language back to a state it has outgrown, they Sanskritise the grammar farther by assigning gender to adjectives, a thing quite foreign to the spoken language. On this point it may be maintained that in cases where the noun of which it is an attribute, is of the female sex,the adjective in spoken Bengali does take a feminine form. This too, I think, is only partially true, if true at all. Buddhimati, rtipubati, sundari are used in connection with the names of persons of the female sex. But such a adjectives have come to be used substantively in the language, and their being regarded as female names has much to do with their application in the current language. That words like buddhiman, buddhimati, &c., are used substantively cannot be disputed. The crucial test of inflection proves that they have become substantives in Bengali. It is enough to mention that buddhimaner, buddhimatike are in use in current Bengali. With regard to sundari, it has further to be said that sundar is certainly used in connection with feminine nouns. At least by people unlearned in the book language.[pullquote][AWD_comments][/pullquote]

Even if the point that a few Sanskrit adjectives naturalised in Bengali still retain in the latter their original feminine forms were fully conceded, it would by no means follow that every adjective taken from Sanskrit should retain the same privilege. That a distinction of gender in adjectives is wholly alien to the spirit of the Bengali language is plain from the fact that no genuine Bengali adjective is ever varied in respect of gender: mota, chhoto, kalo &c., would be used both for males and females, unlike Hindustani which h:is mota and moti, chhota, and chboti, kiila andkali &c. In the matter of gender, as in most other matters, a slavish adherence to Sanskrit bas very much encumbered the written Bengali language.

The union of words by means of Sandhi is a characteristic feature of the Sanskrit language, but not of Sanskrit alone. There is such union in French as d’or from de +or, and in Arabic osda‚Äôrusi – saltanat from dar-ul-saltalant; ud-din from ul-din. In Sanskrit, however, there is more of such union perhaps than in any other human language. Sandhi is a very intelligible, rational process in Sanskrit. by it ‚Äòeconomy of breath’ is secured. But though a rational process in Sanskrit, it is unreason itself when transferred bodily, as it has been, into Bengali. Illustrations will show this best :-Manu + adi=manvadi in Sanskrit. This is very intelligible indeed: ua‚Äô changes, for facility of pronunciation, into va’ or ratherwa‚Äô. What is this Sandhi, however, in Bengali? Manu + adi (in Bengali) = manbadi to the eye and mannabadi to the ear. Bengali Panditsteach, as if it were an unalterable law of nature, that u is changed into b. The bewildered pupil cannot of course see the rationale of this, and be plies hard his memory, therefore, to get by heart what he is taught. Indeed a good deal of stupid docility is necessary tomake one learn the rules of Sanskrit Sandhi as they are taught in Bengal. The object of sandhi in Sanskrit was economy. In Bengali, it is only a mystification and an obstruction. Manu a‚Äôdiin Bengali would be faultless. Manba‚Äôdi would be pedantry merely.

The question of Samas need not detain us long. Samas adds greatly to the power of a language; and it may be necessary to sparingly borrow, from Sanskrit, words compounded agreeably to the rules of Samas. There are, however, genuine Samas compounds in Bengali; which in this respect has a somewhat bigger capacity than Hindustani, which forms only a few compounds of this sort, such as pan-chakki, jeb-katra, &c. In Bengali, however there are lots of such compounds: ‘ambbgach, sosurbari, hatbakso, gamtkata, &c.; are instances. Instead of servile borrowing from Sanskrit in every instance, it would be more rational to avail ourselves of the inherent capacity of our language, and form compounds out of its existing materials. The adoption of compounds like janaika is wholly indefensible; for, to say nothing of the fact that ka+ janais, on psychological grounds, a preferable expression to jana+eka., we have already in Bengali, the expression janek (as in janek-dujon). Janaika, therefore, serves no other purpose than to display before the reader the writer’s knowledge of Sanskrit grammatical rules.

Bengali, though superior to many respects to Hindustani, in the simplicity and logical accuracy of its grammatical structure, is inferior, however, to the latter, in several ways. It is not so self-sufficient as Hindustani is; it is much poorer in its derivatives, and must have, accordingly, to lean more upon its parent tongue, Sanskrit. It has few abstract nouns of its own, derived from current attributive word or common terms. To the attributive terms, mota, lamba, chaora‚Äô, &c. it has no abstract terms to correspond, such as Hindustani possesses in muta‚Äôi, lamba‚Äôi,& c. – Verbs in Bengali have no personal nouns derived¬†from them; there is chala‚Äô, for instance, corresponding to the Hindustani chalna‚Äô, but no word to answer to chalnewala. Kha‚Äôiye, ga‚Äôiye, and a few other words may be mentioned as instances of verb-derived personal nouns; but besides being extremely limited in number, some of them have a. specialised meaning: Kha‚Äôiye means not eater, but a good eater. In respect of abstract nouns derived from verb, such as knowledge from know, Bengali and Hindustani are nearly equally in fault, and both have, therefore, in most cases, to borrow abstract terms from Sanskrit, in the case of Bengali, careful discrimination, however, is necessary. In Sanskrit, abstract terms are formed by adding ta‚Äô, twa, and ya to the attributive root-word. In the current language, abstract terms in ta‚Äô, twa (pronounced tto) andya, which last re-duplicates the final constant of the attributive, and adds thereto the sound of o, are found; but in respect of new importation sit would be best, perhaps, if they could be restricted to abstract terms in ta‚Äô. This particle undergoes no change of sound in Bengali like twa. and ya; and it is besides more consonant to the genius of Bengali to form derivatives by additions at the end simply, without causing any change in the root-word, while ya-formed abstract terms change the vowel sounds of the root word; as for instance, pra‚Äôdhanya (pronounced in Bengali pradha‚Äônno) from pradhana (in Bengali pradha‚Äôn) &c. This latter circumstance gives ta‚Äô no advantage however over twa. Indeed twa in its Bengali form of tto, has. unlike ta‚Äôand ya, been thoroughly naturalised in Bengali. Truly Bengali words like baro & c, form abstract nouns by the addition of tto. The right course for us would seem to be to recognise tto as a Bengali abstract suffix, and to give it a wider extension than at present. Perhaps examples drawn from other languages may help us to overcome our love for twa, which old association has generated. The Latin trinitas has given rise to It. trinita‚Äô, Fr, trinite‚Äô, Sp. trinidad, and Eng. trinity (triniti). When such modifications have been undergone by a Latin abstract suffix, and those modifications are distinctly recognised in the most important living languages, why should not ” similar modification, in Bengali, of a Sanskrit suffix be duly recognised; why should it be kept so disguised by a vicious system of writing as to pass as identical with its parent form?

The want of ordinals may be mentioned as another instance of the natural poverty of the Bengali language. Ordinals are borrowed from Sanskrit; and from Hindustani also, in the single instance of dates. In this latter case, however, the ordinals have become in fact substantives. The genitives of the cardinal numerals do in colloquial Bengali the work of ordinals; duiyer, tiner &c., stand for 2nd, 3rd &c. Often, instead of the genitive form of the cardinal numeral, a noun in the genitive form is used after the cardinal. Thus 3rd day would be expressed, not by tiner din, but by tin diner din. This is no doubt a cumbrous circumlocution, but things must ~ taken as they are.

As regards the ordinals then, since the existing resources of the Bengali language suffice for expressing all that is expressed by means of ordinals, there is no necessity for falling back upon Sanskrit. A larger employment of the genitives of the numerals than is done in the current language seems to be the direction in which writers should work, instead of overburdening the language with the Sanskrit ordinals. When Sanskrit and Bengali numerals do differ but slightly aspa‚Äômch and pancha, an incorporation of corresponding Sanskrit ordinals may not seem to be the introduction of a discordant element. When any of the higher numerals, however, are taken, it is found that the Bengali words by reason of their higher saturation and integration differ greatly from their Sanskrit originals; and in such cases the Sanskrit ordinals, if used in Bengali, would seem highly discordant. Sixty-fifth would be poim-sattir in current Bengali, while the Sanskrit for it is panch-sashtitama. In addition to the reason that such a word, as the last, is not needed in Bengali, its very length ought to be a serious objection. If any borrowing indeed, were necessary in the present instance, I would be more for giving a preference to the handier ordinals of the Hindustani language to their seven-leagued Sanskrit counter-parts, especially as in this very case, there has been borrowing already from Hindustani in the matter of dates, pahla‚Äô, dusra‚Äô &c., being all Hindustani. The Sanskrit ordinals that have been thoroughly naturalised in ‘Bengali are few, as pratharna. dvitiya and dva‚Äôdas. It need hardly be repeated here that I do not in this instance advocate borrowing at all. It is to be mentioned also that our Bengali writers do not confine themselves to borrowing the ordinals from Sanskrit, but borrow, without any necessity whatever, the cardinals also. Eleven, for instance, would be eka‚Äôdas and not egaro; forty, chatta‚Äôrinsat and not challis; two hundred, dui sata and not du-so, twenty-five thousand, pamcbavinsasabasra; and not pomchisha‚Äôza‚Äôr.

Besides those already mentioned there are other derivatives likewise which a cultivated language cannot do without. In our current Bengali speech, for instance, we have a word for man, but none for human,ii a word for do, but none for practicable. In cases where the existing formative powers of the language do not suffice, it would be best to fall back upon Sanskrit. Care, however, should be taken that our language is not unnecessarily burdened; that it is not made to depend more upon the rules of Sanskrit grammar than is absolutely necessary. The object aimed at should be to bring Bengali to a position of independence, and not to keep it perpetually in leading strings. Indiscriminate borrowers from Sanskrit ought again to remember that in master the rules of Sanskrit grammar requires a considerable expenditure of brain power, and that if Sanskrit grammatical forms are to pass current in written Bengali, a large number of human beings will have to incur such expenditure for the acquisition of knowledge of a most elementary kind even. But more of this hereafter.

The question of grammatical forms being now disposed of, the even more important question of vocables may now be taken up. The inflected forms of words, as well as other derivatives, are indeed vocables, inasmuch as they have each an independent existence in the language. What has been said, about grammatical forms and derivatives covers therefore a part of the present subject. Grammatical forms and derivatives fall under a few general laws, however; and these laws form but a small item by the side of the numerous body of main words, which, though originally significant of attribute, have come to be now mere conventional symbols for objects and ideas. What is to be said here about vocables maybe understood to apply to this latter class of words.

The vocables use in Bengali, written and spoken, are divisible into three classes. (I) Sanskrit-derived words, but so much altered from their original form as to have necessitated their being written differently from Sanskrit. (2) Sanskrit words bodily transferred, which, though retaining their original spelling, are for the most part pronounced in a peculiarly Bengali way. (3) Words of non-Sanskrit parentage.

The first class of words forms the great body of the spoken language. In the written language, however, they are seldom admitted except in dialogues. Their Sanskrit originals, as a rule, get the preference, and they themselves are cast aside as vulgariii In mere introductory primers current words are for the most part employed, but side by side with them, there occur also their Sanskrit originals. If there are such words as bhai’, ka’l(to-morrow), ka’n, chok, sona’ (sona) &c., there are also bhra’ta’, kalya’,karna’, svarna, &c. It seems, colloquial words are employed at all simply because there is no doing without them. The child knows them and knows no others, and must be first taught to read by means of words that he knows, and not by means of their learned equivalents. But the great object aimed at is to reach the pupil such equivalents in as much profusion and within as short a time as possible. So soon, therefore, as he has mastered the difficulties of Bengali alphabetic writing, one important part of his education comes to be the acquisition of Sanskrit vocables accompanied by a sedulous inculcation on the part of the teacher, that in writing, these vocables should be always employed in lieu of Bengali words that he is familiar with.

Every child in Bengal that learns to read has to learn the Sanskrit equivalents of the commonest names. He has learnt to call copper ta’mba’, leaf pa’ta, head ma’ta’, horse ghomra’, rice cha’ll and so forth; but these be must discard for ta’mra, patra, &c. What is the earthly good of all this, it is not easy to see; and yet the fact is nothing less than what it is here stated to be. The case is just as if every French child that learns to read and write were taught to write ferrum for fer, aurum foror, and so on to rite end of the lexicon. From such a heavy and galling. but most unnecessary burden, deliverance is certainly desirable; but an established order of things must have numerous adherence, so that deliverance may be slow in coming after all.

The displacement of familiar Sanskrit-derived Bengali words by their Sanskrit originals can be justified on no reasonable grounds. The ousting of words of non-Sanskrit origin, whether aboriginal or foreign, is equally indefensible. Purism is radically unsound, and has its origin in a spirit of narrowness. In the free commingling of nations, there must be borrowing and giving. Can anything be more Absurd than to think of keeping language pure, when blood itself cannot be kept pure? No human language has ever been perfectly pure; any more than any human race has been pure. Infusion of foreign elements do, in the long run, enrich languages, just as infusion of foreign blood improves races. Seeing then that languages, as men speak them, must be mixed, impure, heterogeneous; to reject words like gorib (Ar. gari’b) and da’g (Ar. da’g) &c., from books, on account of their foreign lineage would be most unreasonable. Current words of Persian or Arabic origin connect us, Hindus of Bengal, with Musalma’n Bengalis, with the entire Hindustani-speaking population of India, and even with Persians and Arabs. Is it wise to seek to diminish points of contact with a large section of our fellow countrymen, and with kindred and neighboring race, with whom we must have intercourse, in order that we may draw closer to our Sanskrit-speaking ancestors?

Human happiness would seem to be better promoted by increased points of contact with living men than by increased points of contact with remote ancestors. But men are very often swayed in these matters by sentiment more than by reason. The feeling that impels Bengali Hindus towards Sanskrit is perfectly intelligible. With Sanskrit are associated the days of India’s greatest glory, with Persian and Arabic the days of her defeat, humiliation, and bondage. The budding patriotism of Hindus everywhere would therefore naturally eschew Persian and Arabic words as badges of slavery. In the long run, however, considerations of utility are sure to over-ride mere sentimental predilections.

It should be understood that I do not advocate any fresh introduction of Arabic and Persian words, but¬† insist only on the desirability of giving their fulliv¬†rights to such words as have already been naturalised in the language anti are in everybody’s mouth. Persian and Arabic words used by Bengali ignorant of those languages ought to be accepted as right good Bengali. As a matter of fact, many such words, those connected with Law especially, are employed in writing; but the purist spirit is still very active, and a disinclination to admit such words into writing is yet but too common.

Not only does written Bengali, as a rule, seek to supplant current Bengali words by their Sanskrit equivalents; it keeps alive also the antiquated, obsolete forms of current words. These, having once obtained a recognised place in the language of writing, now refuse to be ousted from it. We call rice cha‚Äôl, but write it chaul, pa‚Äôthure (stony) similarly becomes pa‚Äôthuria‚Äô, and the Node of colloquial speech is Nadia‚Äô in writing. But I need not multiply instances. So numerous are such differences that an inveterate¬†notion seems to have gained a firm hold of the national mind that the current form of a word is ‘not the correctv¬†form.

I look upon this as a most unfortunate thing. The struggle with Sanskrit alone is no light affair, backed as Sanskrit must be with the entire bias of learning and wide-spread association; and Sanskrit here has a potent ally in the obsolete forms of words rendered classical by Kabikankan, Krittibas, Kasidas, and Bhiratchndra.

The substitution of Sanskrit for current familiar words and of obsolete for current forms of a certain class of words may both be included under the head of ‚Äúcalling common things by uncommon names.” Most of our writers are fully under the sway of this supposed purity-of-style fetish. It is amusing to contemplate the strange shifts to which even our best writers are driven to avoid current expressions. An illustration will show this best. A writer of deservedly very high reputation has recourse to utkhep (utksbep) karia‚Äô punarbar haste grahan kara‚Äô, as a substitute for the common expression lopa‚Äô. Can anything be more awkward than this?

The rage for Sanskrit vocables manifests itself in matters, in which learning would seem to have little room. On the license plates of boats that ply in the river Hugli are to be seen nabik and arohi as the Bengali for crew and passenger respectively; but none of the crew of any boat, and ninety-nine hundredths of the passengers, have no notion of what the words nabik and arohi mean. Language has its many sides, and it is but reasonable that the carpenter, the boatman, the shoemaker should give the law in matters connected with carpentry, boat-rowing and shoe making respectively; while in matters connected with science or scholarship, the savant or scholar should he the supreme arbiter. In Bengal, however, the Sanskrit-knowing Pandit has in a large measure assumed the function of determining the written language in all its aspects. The mental characteristics of the nation, and its historical antecedents have of course helped to bring about this result.

The present practice of borrowing from Sanskrit is based on no definite principle. Rational borrowing should seek only to supply a felt wait. Where words are really wanting in Bengali, there must be borrowing. But such borrowing as has been above described is grounded on no necessity. No limit is set in fact to the extent to which words are to be borrowed from Sanskrit, so that every Sanskrit word is considered to have a rightful claim to be incorporated into Bengali. Is this to enrich the language or to over burden it? This indeed is carrying us back into the past with a vengeance. In the early flexible stage of Sanskrit, when its formative powers were active, whole hosts of words were formed to express the same thing. Those words were then, as philologists hold, transparent attributive terms, and not the arbitrary symbols that they afterwards became. Men could not, indeed, lie so irrational as to invent more than one arbitrary symbol for one and the same thing. Among the many significant symbols expressive of the same idea, there was a struggle for existence and a survival in the long run. of the fittest. More terms than one have in many cases survived; but on a priori grounds it is quite impossible that more than one could survive at the same spot; and among the same class of people. Distance of place, or peculiarities of social organization, by limiting intercourse, could alone cause a selection of different names for the same thing. There has further been a differentiation of meaning between words that originally meant exactly the same thing. Our Sanskrit School of writers would, however, undo all this. They would bring back the dead to life. They would restore to Bengali, which is one of the modern developments of Sanskrit, all the imperfections of the mother-tongue, that have been cast off for good. What a terrible legacy would a wholesale appropriation of the Sanskrit vocabulary leave to posterity? Men of capacity little think of the labor that the acquisition of a. language costs; and of this labor the heaviest part is that required in mastering the vocabulary, which, consisting as it does for the most pan, of arbitrary symbols, is dull, dreary matter to learn. Where arbitrary symbol furnish a key to valuable knowledge, the symbols ought surely to be learnt. In the present case, however, the labor spent on the acquisition of words would he vain, meaningless labor. What is the good of learning a new word where one does not learn a corresponding new idea with it?vi Perfection of language requires that no two words should express exactly the same idea, and that no two ideas should have the same name. No human language is indeed perfect like this, it is true. Due this is no reason why we should work the other way, and goon sanctioning and accumulating defects.

The example of other languages is quoted as a ground for maintaining, and even widening existing differences between spoken and written Bengali. No doubt there are numerous instances in other languages of calling common things by uncommon names. This, however, cannot be looked upon as desirable on any account, and there is a visible tendency in English, at any rate, to assimilate closely the written to the spoken tongue. Dean Alford tells us, that the tendency to ‚Äòcall common things by uncommon names’ varies inversely as the writer’s culture’; and a late professor of English at the Presidency College used to say, that in England, at the present day, the language spoken by the highest and best-educated has more in common with that of the lower orders than with that of men of inferior education. In taking a survey of the language of a country, the form of it peculiar to any large class of men, such as the men of inferior education in a community must form, is not of course to be left out of account. But the language of the class that stands highest in culture and social position is the standard to which the language of all sections of the community has a tendency to converge. The language of the highest and the most cultivated must be taken then as the normal standard of the language, and in the best English writers the tendency to ‘call common things by uncommon names’ must be as its minimum. Indeed, so far as the cultivated and the uncultivated go together, common sense should dictate that there should be community of language. If indeed the object were to confine knowledge to a caste, there could not be a cleverer contrivance than to make the written language diverge widely from the spoken. Such a contrivance would carry with it its own Nemesis, however. Besides the unnecessary waste of brain-power implied in the acquisition of mere words without additional ideas, there must inevitably result a deterioration of the intellect when it busies itself with mere word-knowledge.

In dealing with the question of the employment of Sanskrit words in Bengali writing, the Bengali graphic system cannot be left out of account. This system is nearly as bad as the English; it departs nearly as much from correct phonetic representation as the latter. This however is a wide question in itself, and need no there be further noticed than its direct bearing upon the Sanskrit element of book-Bengali demands. The Bengali pronunciation of Sanskrit is as monstrous as the English pronunciation of Latin is or was till vii  lately; and the Sanskrit words admitted into Bengali are of course all mispronounced, so that they are Sanskrit only to the eye, but not to the ear. This shows that the despised vernacular can, after a certain fashion, assert its rights against unjust encroachments. Let us come now to illustrations. The current Bengali equivalents of fish and sun are ma’ch (old Bengali machh) and suji respectively. In books mach is made to give way to the Sanskrit matsya and sujji to surjya, but instead of being pronounced as they are written, which, by the way would be the correct Sanskrit pronunciation, they are pronounced motso and surja respectively. We acquire mach and suji as a part of our mother-tongue, and the conventional necessity of having further to acquire their corrupt Sanskrit equivalents mot so and surja, I, for one, must deplore as almost oppressive and unprofitable burden.

There is another class of words which are wrongly accounted to be the same in Bengali as they are in Sanskrit. The Bengali and Sanskrit equivalents of south and lord, for instance, are written alike in both the languages; but while in Bengali, they are pronounced as dokkhin and Issar respectively, in Sanskrit they are dakshina and is vara.

It is plain then, that the so-called Sanskrit words in use in written Bengali are in fact neither Sanskrit nor Bengali, but monsters one knows not to call what. The unwise and indiscriminate transfer of Sanskrit words into Bengali has another bad effect little thought of. Certain sounds in Sanskrit are converted into certain other sounds in Bengali, according to definite laws, such as S. into S. These laws cannot be transgressed. Mispronunciation of Sanskrit words introduced into Bengali is therefore a sort of necessity, and this mispronunciation is imported back into Sanskrit, while the Bengali learns that language. The correct pronunciation of Sanskrit, if enforced in our schools and Colleges, would be a most effective check on the present practice of indiscriminate borrowing from Sanskrit. But on this point hereafter.

বাছবিচার

Latest posts by বাছবিচার (see all)

- (বাংলা-ক্লাসিক) বিশ্বনবী – গোলাম মোস্তফা [শর্ট ভার্সন।] পার্ট ৫ - মার্চ 17, 2024

- বাংলা প্রচলিত হবে যে সময় শিক্ষকরা প্রথম প্রথম একটু ইনকমপিটেনটলি (incompetently) কিন্তু পারসিসটেনটলি (persistently) বাংলায় বলা অভ্যাস করবেন (১৯৮৫) Рআবদুর রাজ্জাক - ফেব্রুয়ারি 26, 2024

- ভাষার ক্ষেত্রে গোঁড়ামি বা ছুৎমার্গের কোন স্থান নেই Рমুহম্মদ শহীদুল্লাহ্ - ফেব্রুয়ারি 21, 2024